Ticks! Just thinking about them can make your skin crawl. With growing populations of ticks in northern New England, there is a good chance you or someone you know has been bitten by one. Tick bites are a concern because certain species can transmit diseases.

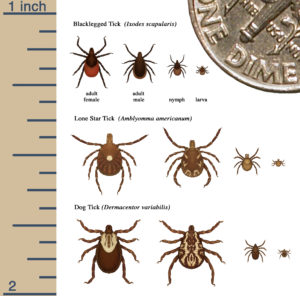

The tick we worry about most in our region is the black-legged tick, also known as the deer tick, which can carry Lyme disease. Recorded cases of Lyme are increasing across northern New England. Besides Lyme disease, various types of ticks in the region can transmit anaplasmosis, babesiosis, Borrelia miyamotoi, ehrlichiosis, and Powassan virus. While symptoms of tick-borne diseases vary, they typically include flu-like symptoms such as fever, headache, chills and body pains.

Ticks are most active in late spring and early summer when young ticks, known as nymphs, are looking for an animal to feed on, and then again in October and November when adult ticks are looking for another meal before colder weather arrives. Some species, including the deer tick, are active whenever the temperature is above 40 degrees, even in the winter.

New potential concern

Many recent reports have focused on the lone star tick, which is found throughout the eastern and southern United States. This tick’s range may extend to the southern edges of northern New England, but cases of lone star tick bites in the region are rare. Experts suspect most of these cases are the result of people traveling to other areas, where the lone star tick is more established. However, this tick’s range is likely to expand, and health departments in our region are monitoring the situation.

Lone star ticks are typically easy to identify. Females have a single white or gold dot, or “lone star,” on their back, while males have white spots or streaks on the outer edge of their body.

Lone star ticks can carry several diseases, including Bourbon virus, Heartland virus, southern tick-associated rash illness, tularemia, and ehrlichiosis. The most attention-getting reports have involved cases of allergic reactions to red meat following bites from lone star ticks. Scientists are still working to better understand this connection.

Keeping track of the problem

The northern New England states are interested in monitoring ticks. The University of Maine Cooperative Extension and the New Hampshire Department of Agriculture offer free tick identification, while Vermont has a crowd-sourced tick tracker that you can contribute to.

How can you prevent tick bites?

When possible, avoid tick habitat, such as wooded and brushy areas with high grass and leaf litter.

If you are going into tick habitat, follow these steps:

- Treat your clothing and camping gear with a product containing 0.5% permethrin, carefully following the instructions on the product label. Pre-treated clothing and gear are also available from some stores.

- Wear light-colored clothing to make it easier to spot ticks crawling on you.

- Wear long pants and socks and tuck your pant legs into your socks.

- Use an EPA-registered insect repellent such as DEET.

- Check yourself, your children, your pets and all clothing as soon as you come back inside. Shower as soon as possible.

- If you do find a tick, remove it as soon as possible using fine-tipped tweezers. The CDC has full instructions.

If you develop symptoms after a tick bite, contact your health care provider.

For more information

The CDC has a thorough guide to common ticks in the United States and the diseases they carry. In addition, the Northern New England Poison Center can be a resource for questions about tick bites and tick-borne diseases. Call 1-800-222-1222, chat online or text the word POISON to 85511.